There are so many terrible legends about what happens behind the walls of psychoneurological dispensaries! In stone bags with tiny windows there are madmen who rush at the orderlies at every opportunity, and the latter, in turn, beat the patients with rubber batons and “treat” them with electric shock! So?

Of course, in the 21st century everything looks much better: hospitals are clean, sterile, and physical force is used extremely rarely. But electroconvulsive therapy is still used today - it is one of the last relics of the brutal psychiatry of the 19th century. Let us ask ourselves: how cruel?

In 1887, 23-year-old journalist Nellie Bly quit her job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch, tired of covering theater premieres, and figured out how to make a report that could bring her real fame and recognition. Of course, she was guided not only and not so much by egoism. First of all, she was motivated by philanthropy.

In just one night, Nellie rehearsed - her theatrical experience helped her - the behavior of a schizophrenic, and the next day she rented a room in a cheap house for workers. All day long she drove the owners of the house to white heat, running to them from her room and reporting either about giant rats or about monsters in the closet, and calling them crazy killers. Quite quickly, Nellie was considered crazy, the police were called, and a few days later, after an examination that confirmed her insanity, the girl ended up in the New York psychiatric hospital Bellevue.

Nellie Bly trains to feign madness

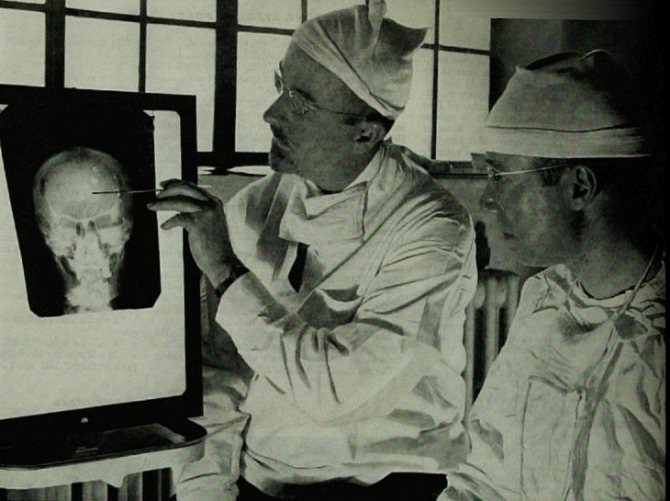

Nellie Bly is examined by a psychiatrist (drawing from the first edition of the book “Ten Days in a Madhouse”)

Bly spent ten days in the hospital and was amazed at the unsanitary, anti-scientific, inhumane conditions in which the patients were kept. For most of the day - from six in the morning to eight in the evening - the patients were tied up, sitting on wooden benches, and they were not given any protection from the cold. They were fed spoiled beef and stale bread rejected by farms, and they were given dirty water to drink. Patients were not allowed to go to the toilet at odd hours, they constantly defecated on themselves, and no one cleaned it up. The hospital was full of rats. The patients did not receive any treatment other than blows with sticks. They washed them by dousing them with ice water.

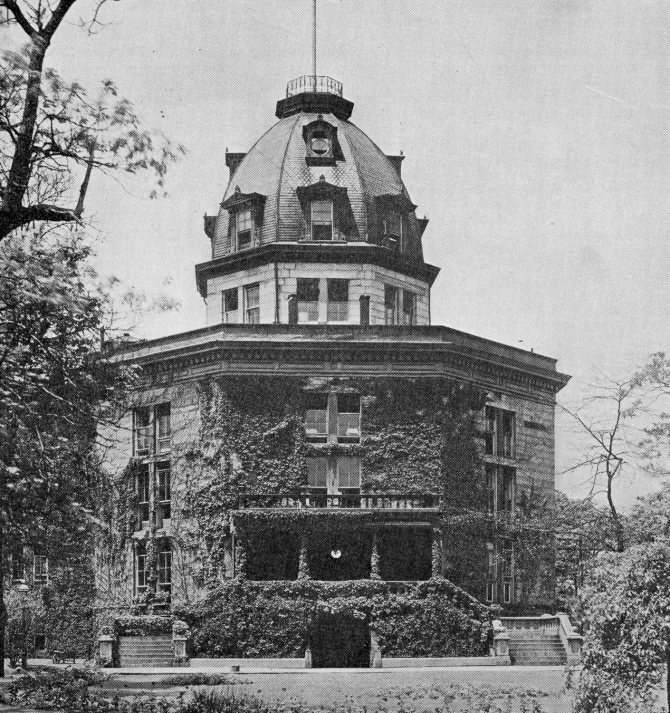

The Octagon on Roosevelt Island is the main entrance to the very hospital where Nellie Bly spent ten days. Photo from 1897

Nellie Bly hairnet packaging. Accessories with a portrait of the famous journalist sold out instantly

Ten days later, Nellie was taken from the hospital by employees of The World newspaper, with whom she had agreed in advance to prepare the material. Her report did not fit into the length of the article and was published separately in the form of a book, “Ten Days in a Madhouse.” The publication became a sensation; In the same year, 1887, a trial was held, police were sent to the hospital, and Nellie Bly became the main witness in the case of abuse of patients.

This was a turning point. After the end of the scandal, which resulted in many heads rolling - the investigation affected a number of mental hospitals - significantly more funds began to be allocated to psychiatry, hospitals began to be inspected, and methods of “cure” began to change rapidly. In essence, Nellie initiated a revolution, a transition from medieval “medicine” to modern one, and paved the border between two eras.

Well, let's see what happened “before”, what it turned into “after” and how things are now.

From time immemorial, madness was considered the machinations of demons, evil gods, the devil, the highest punishment, that is, not a physical disease, but a mystical one. Whether in Ancient Greece or Rome, or in Babylon or China, madness was never perceived as something requiring direct human intervention. In the same Greece, some types of madness were considered sent down by the gods not as punishment, but for good, since the madman acquired extraordinary abilities - for example, he began to see the future.

One way or another, there was no generally accepted attitude towards those who had gone mad. They were shunned and praised, ignored or treated like ordinary people. If the sick were “treated”, it was only through prayers. Therefore, the pre-Christian period is not very interesting to us.

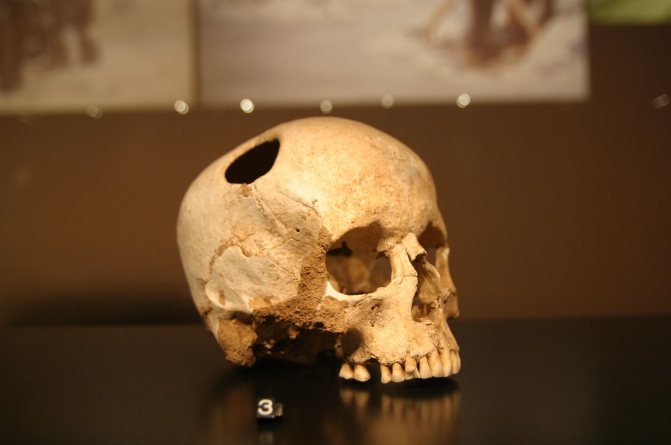

Trepanned skull from the Iron Age. According to research, the patient lived for some time after the operation

However, one surgical method appeared in the rudimentary “psychiatry” long before our era - trepanation. For example, in Sumerian burials you can find skulls with neatly drilled holes.

Trepanning methods reached their greatest flourishing in Mesoamerica, which developed much more slowly than the Old World before the intervention of Europeans, and by the 13th century reached the level of civilization that Europe and Asia had achieved one and a half thousand years earlier. Trepanned skulls are regularly found in excavations of Aztec burials, and analysis shows that people with holes drilled in their skulls sometimes lived for several years after the operation.

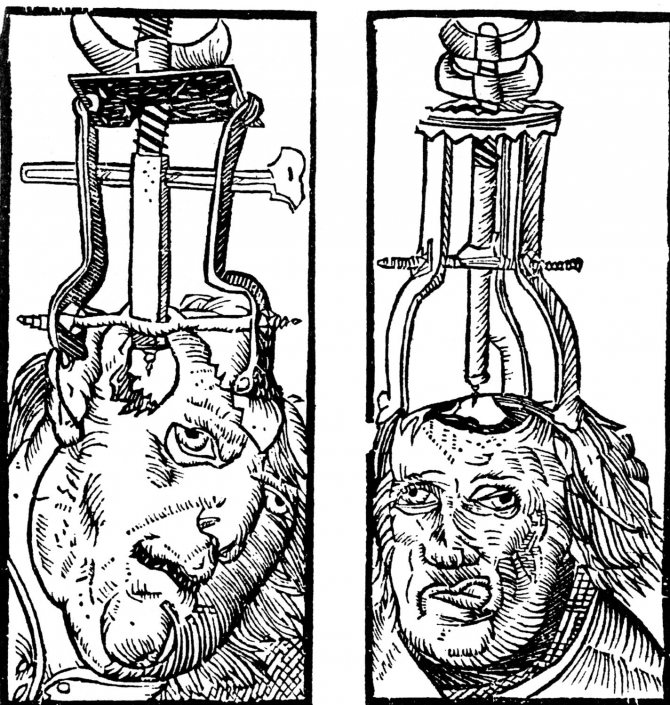

Engraving depicting the process of trepanation, from a medical book published in 1525

In Europe, the first trepanned skulls date back to the Neolithic period - several dozen skulls with cutouts have been found in stone dolmens today. The cutting techniques were varied: a square section of the skull was cut out with notches, and ring-shaped drills were also used; sometimes the skull was chiselled with a narrow tool resembling a chisel, knocking out triangular holes tapering downward.

The main question is why this was done. The reasons were very different: for example, trepanation was used to remove fragments resulting from skull injuries, or to cure a patient of headaches. As a cure for madness, trepanation worked quite simply: through a hole in the skull, evil spirits left the patient's head. One way or another, trepanation led to death in more than half of the cases, but it was not something cruel, inhumane, or violent. The doctors simply did the best they could.

Removing the “stone of madness” from a patient’s head, the work of Hieronymus Bosch

European Christian civilization perceived madmen exclusively as possessed by demons or demons. Sometimes they were left untouched, sometimes they were killed, sometimes they were forced to work. Until the 18th century, the main way of subsistence for madmen was begging. The holy fools were served - or not served, they were looked at with disgust - or with laughter.

There was a strange logical inconsistency in this: on the one hand, a madman was perceived as sick, but on the other hand, he did not need to be treated, like, for example, a wounded person or someone with a sore throat. Although trepanation was still periodically practiced - mainly in relation to fairly wealthy patients who suffered, for example, from attacks of epilepsy or migraine.

Vasily Surikov, “The Holy Fool Sitting in the Snow,” 1885. In the Russian tradition, “madness in the name of Christ,” that is, holy foolishness, was perceived as a gift from above; holy fools were revered and listened to

They really began to treat the insane only with the development of science, during the Industrial Revolution. In the enlightened 18th century, treatises, scientific works and recommendations for curing the insane appeared - and sometimes in comparison with them, manuals for burning witches seem like a children's fairy tale.

"William Norris, the Madman of America" is an 1814 engraving showing conditions at Bethlem. Norris spent more than twenty years in chains

The first institutions for keeping the insane appeared in the 15th century, but over the next three centuries they did not perform a therapeutic function. Dispensaries were nothing more than prisons, allowing the insane to be separated from society, isolated, and the city streets cleared. The “patients” were simply chained to the walls and sometimes fed - that’s all. Please note that Nellie Bly discovered exactly the same conditions in a central New York psychiatric clinic at the end of the 19th century!

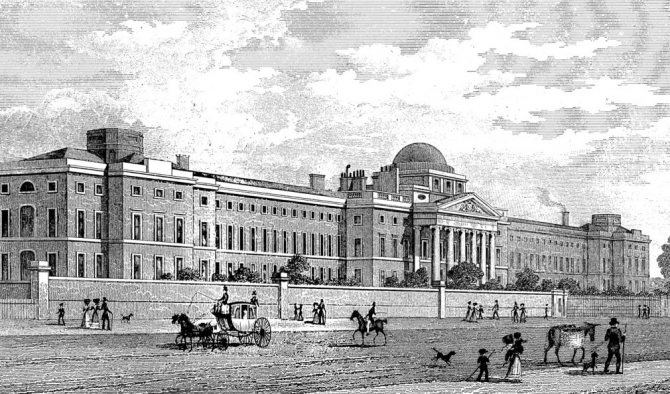

Perhaps the most famous European hospital was the Bethlem (that is, “Bethlehem”) Royal Hospital near London - it was from the distorted “Bethlem” that the word “bedlam” came, the meaning of which, we believe, does not need to be explained. Founded in the 14th century, Bethlem became a refuge for the mentally ill in 1547, when ordinary patients were no longer brought here, concentrating all efforts on the insane.

Initially, there were few patients, but in 1675 the hospital was forced to move to a new complex of buildings, as the number of mentally ill people was inevitably growing. The latter, by the way, served as the main source of income, since for a few pence anyone could walk along the hospital corridors and look into the cells filled with screaming, kicking and angry madmen. A healthy person who, by the will of fate, ended up in such an institution, went crazy in no more than a few months.

The new, third building of the Bethlem Hospital (1828 engraving)

This is exactly what almost all European hospitals for the mentally ill remained for several hundred years. The same Bedlam “corrected” only in 1816, and then after a significant scandal. At the beginning of the 18th century, another expansion was required, and a new building was designed for the hospital - no longer as a prison, but as a hospital, with large windows and wards.

Nevertheless, Thomas Monroe, who took over the post of chief physician of Bethlem at the beginning of 1816, had no intention of changing customs, and the prisoners were just as chained to the walls in the new building as in the old one. In June of the same year, after a visit to the hospital by an inspection commission, Monroe was removed, and conditions in the hospital began to gradually change: prisoners began to be allowed out for walks, a library and a dance hall appeared.

Bedlam patients in the 1850s

However, it would be unfair to say that hospitals in the 19th century did not treat patients at all. They were given bloodletting (because they were done to all sick people, regardless of illness), and fed opium and hellebore. There was not the slightest sense from all this, but the patients behaved calmer, became weaker, slept a lot and lived for a short time, which made it easier for the overloaded insane asylums.

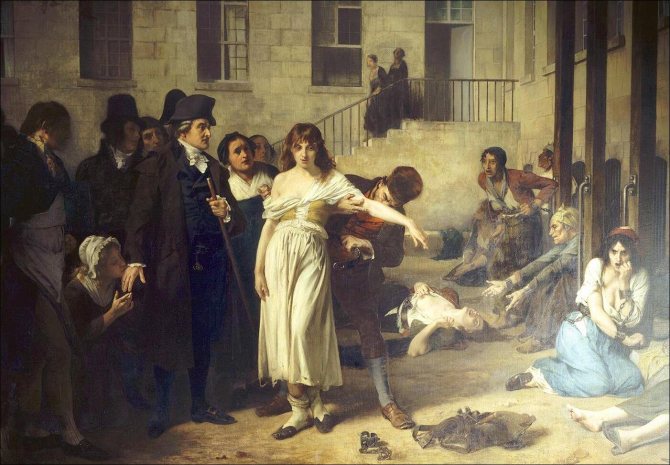

A revolutionary in the field of psychiatry was the Frenchman Philippe Pinel. In 1792, at the height of the French Revolution, he became the head physician of one of the largest institutions for the mentally ill, the Bicêtre Hospital. Taking advantage of the political confusion, Pinel managed to obtain permission from the revolutionary authorities to remove the chains from the patients.

The king would never agree to such a thing, but the Convention perceived the mentally ill as prisoners of the monarchy, and therefore Pinel easily received the required document. He turned out to be right: without chains, patients did not become more dangerous. On the contrary, the general mood in the hospital increased and the incidence of self-harm decreased significantly. Following the example of the Bicêtre hospital, by the end of the 18th century all hospitals got rid of chains.

"Philippe Pinel at the Salpetriere". Removing the chains from the mentally ill, thin. Tony Robert-Fleury

Despite the fact that Pinel wrote a number of works on psychiatry, neither he nor anyone else at that time found any adequate way to treat the mentally ill. Hospitals were still prisons, albeit without chains.

However, the improvement of conditions in psychiatric hospitals occurred very slowly. Pinel removed the chains, but there remained walls, closed stone bags, sticks as treatment, constant malnutrition and unsanitary conditions. Such conditions prevailed throughout Europe, although it should be noted that in 1784 another breakthrough occurred in Vienna - for the first time, a building was built specifically designed to house the mentally ill. The Narrenturm tower has survived to this day - its gloomy chambers now contain exhibits from the National Pathological Museum; In addition, the tower is famous for the fact that on its roof there is one of the oldest lightning rods in the world and the oldest in Europe.

The Vienna mental hospital tower Narrenturm was completed in 1784. Today it houses a pathological museum.

By the end of the 19th century, a wealth of psychiatric research had emerged. In homes for the mentally ill, normal sanitary conditions, individual wards and beds were gradually introduced, and prisoners received relative freedom of movement. The famous investigation of Nellie Bly shook up the public so much that by 1900 there was apparently not a single institution in the world where patients were treated like cattle, although twenty years earlier the technique of immobilization, isolation and feeding with opium was widespread and in the Old and New Worlds.

But in the same 19th century, another difficult period for psychiatry began - let’s call it “scientific”. Theoretical studies and observations of patients, which were initiated by Pinel, led to a self-evident result: the need to somehow treat patients. This is where the second circle of hell began.

Pinel, like his predecessors, believed that the basis of treatment should be to calm the patient - but, of course, not with bloodletting (although he allowed them as a last resort). He prescribed warm baths, antispasmodic drugs, camphor, opium, and laxatives to his patients. That is, despite all the progressive changes, the great Frenchman did not advance beyond medieval concepts of treatment - like many who continued his work.

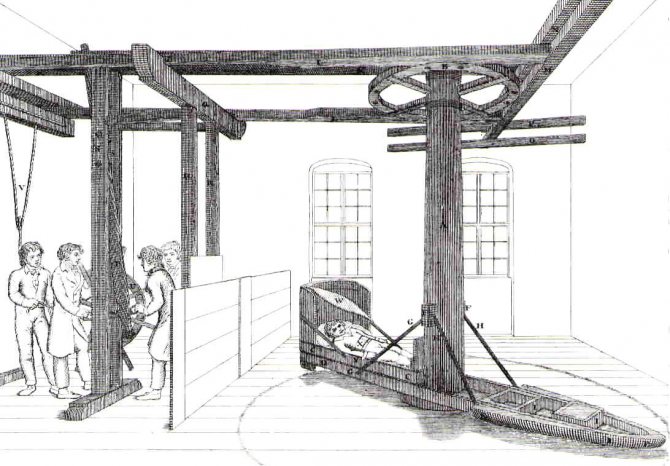

Rotating centrifuge bed for treating the mentally ill

Long before Pinel, some psychiatrists tried to cure patients in unusual ways, but they walked blindly, pointing their fingers at the sky. For example, the Flemish physician Jan Baptista van Helmont proposed the “water shock” technique at the beginning of the 17th century. Quite by accident, he saw one of his patients nearly drown while washing himself - and after that he became almost normal.

Van Helmont suggested that shock and fear of death could have a positive effect on the traumatized mind. He took a medieval torture wheel as a prototype for a water shock apparatus. The patient was tied to a wheel, and then lowered into the water and brought almost to the point of drowning - but not to the point of losing consciousness! Despite the extremely low recovery statistics, van Helmont noted that some patients became calmer, more reasonable and sane, even to the point of complete recovery.

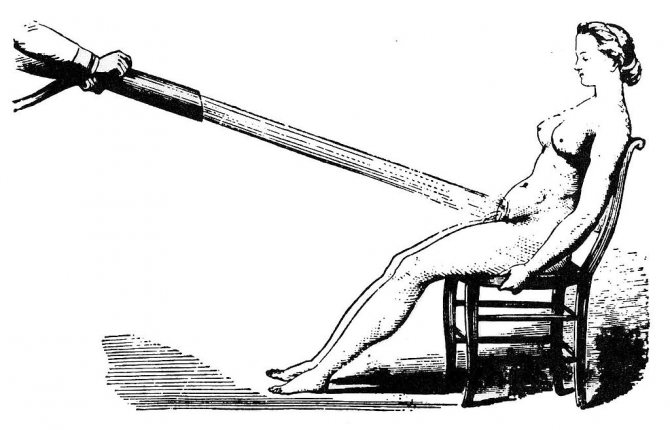

Water procedures were also used to treat hysteria, which at that time was considered an exclusively female disease. It was believed that for this it was necessary to stimulate the patient's genitals

Subsequently, already in the 18th-19th centuries, van Helmont’s technique was widely used in American hospitals. For example, the experiments of Dr. Samuel Willard (1748-1801), the head physician of the psychiatric clinic in the city of Uxbridge (Massachusetts), are known. Willard developed a special tank with portholes, where he immersed patients and brought them to almost complete drowning, causing “water shock.” Judging by the doctor’s notes, there were no recoveries among them. In Willard’s defense, it must be said that he made a huge contribution to the fight against smallpox: he single-handedly persuaded the city council not to ban the “suspicious” vaccination process and thereby saved several hundred lives.

Another well-known curiosity was the attempt of the French doctor Jean Denis to cure the mentally ill by transfusing them with sheep's blood. The year was 1667, blood transfusion was in its infancy, but, according to the doctor’s notes, his patient Arthur Goga survived and even became more reasonable. Denis argued that transfusing the blood of a clean animal would expel the patient's diseased blood, reducing the demon's influence on his mind. True, Denis’s second such experiment, carried out in France (he treated Goga in London), led to the death of the patient. The doctor was accused of premeditated murder and executed.

"Relaxing chair"

Experiments with transfusion (as well as “water transfusions”) continued into the 19th century. Benjamin Rush himself (1746-1813), the father of American psychiatry, bled patients and replaced it with “healthy” blood from normal people. During his experiments, Rush killed several dozen patients, but at the same time made enormous contributions to psychiatry and other areas of medicine. He was the first to introduce the concept of “occupational therapy” (which today serves as one of the main methods of treating the mentally ill) and described a number of typical syndromes (including the hitherto unrecognized “savant syndrome”).

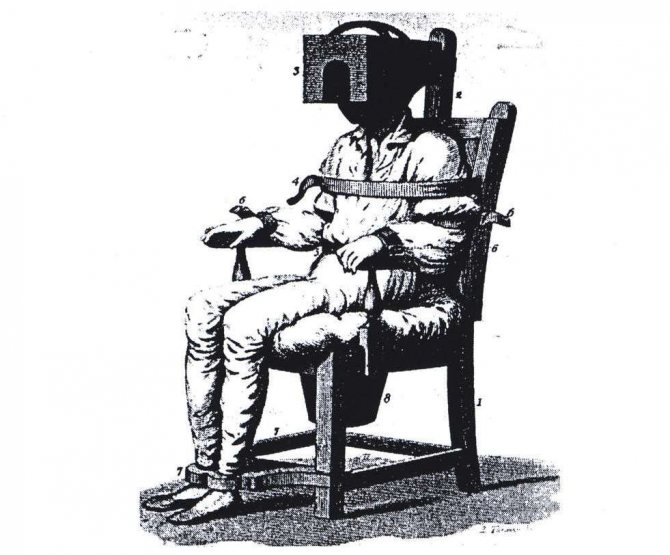

Rush came up with many creepy ways to cure a mentally ill person. For example, in 1811 he patented a “resting chair,” which was a wooden chair with straps for the legs, arms, and a wooden head-restraining box. The patient in such a chair was absolutely helpless and motionless.

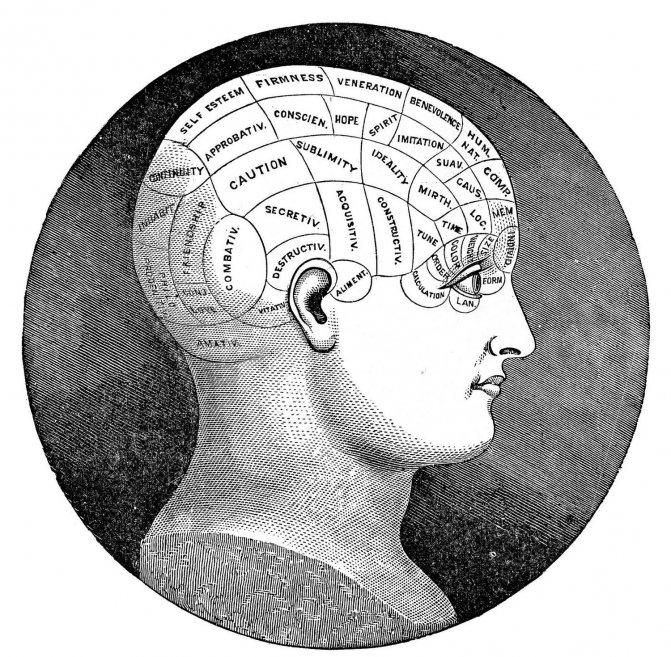

When talking about psychiatric misconceptions, one cannot fail to mention Dr. Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828). He introduced into medicine the concept of phrenology - the science of the connection of the human psyche with the shape and relief of the skull. Gall “tied” human qualities to various parts of the skull; if any part was convex, the corresponding quality was well developed in the person. The inconsistency of phrenology was finally proven only in the middle of the 20th century. Gall himself did not do too much harm to patients, but his followers, phrenologists, often performed trepanations of certain parts of the skull precisely to change the patient’s psyche. The lack of results bothered few people.

Gall's classic phrenological scheme, which, after proving its inconsistency, gave rise to a huge number of parodies and caricatures

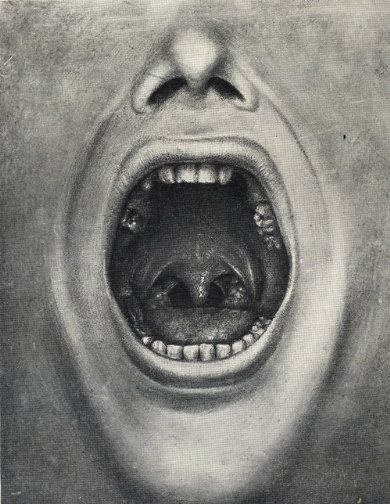

A typical illustration from Cotton's book on the infectious nature of madness. The infection, according to the doctor, was contained mainly in the teeth, and Cotton recommended tearing them mercilessly

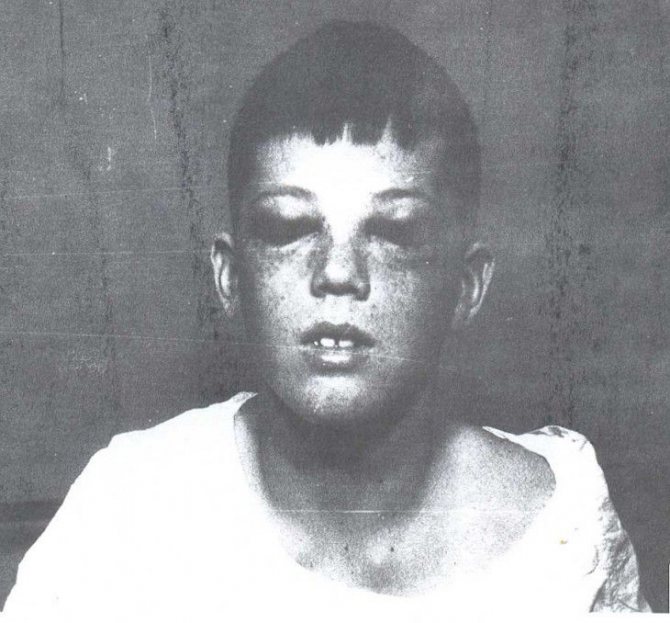

Surprisingly, similar misconceptions arose in psychiatry much later, at the beginning of the 20th century. The famous American physician Henry Cotton (1876-1933), for example, suggested that mental illness is the result of an infection affecting one or another part of the body. Cotton treated his patients by... amputation. By removing the infected organ in time, Cotton - as he himself believed - stopped the spread of the bacterium, which, if it entered the brain, could cause sleepwalking.

A dentist by trade, Cotton removed more than 11,000 teeth between 1919 and 1921, and sometimes amputated jawbones, fingers and genitals. The mortality rate of his patients reached 43%; Nevertheless, Cotton's clinic was for a long time considered very progressive, and Cotton was perceived as a luminary and innovator of American psychiatry.

This creepy direction of medicine deserves special attention. Actually, lobotomy itself is a branch of a vast branch, psychosurgery.

Definition

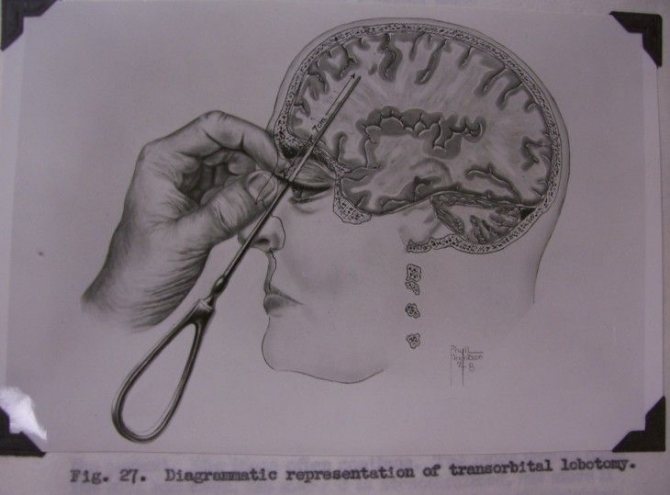

Lobotomy is a psychosurgical operation, the task of which is to change the functioning of the frontal or other lobes of the brain, including those responsible for self-determination and self-awareness of a person, through surgical intervention. In this case, either the connections between adjacent lobes are interrupted, or the white medulla is removed, due to which the operation received an alternative name - leucotomy. To do this, a special tool is used - a leukotome, which resembles a small knife for chopping ice.

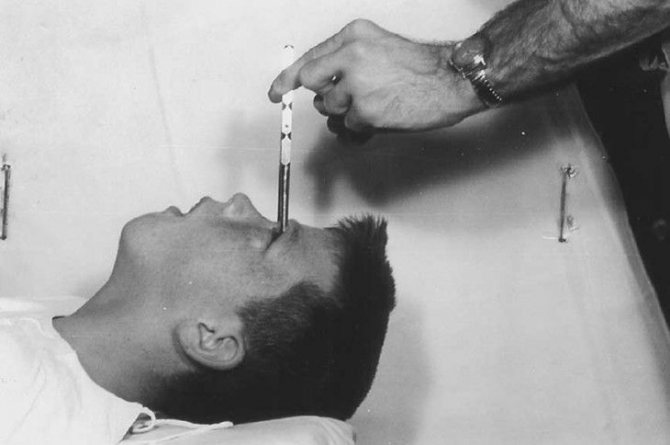

There were several types of lobotomy. For example, when performing an operation such as a transorbital lobotomy, the doctor inserted an instrument into the patient's eye socket, thus reaching the desired areas of the brain, and then cutting them. In prefrontal lobotomy, holes are drilled or punched into the patient's skull to interfere with the brain. This is a rather scary operation, but some patients who underwent such an intervention experienced an improvement in their psychological state, however, such cases were few.

Surgically induced childhood

Freeman coined a term for people who had recently undergone a lobotomy: surgically induced childhood. He believed that patients' lack of normal mental abilities, distraction, stupor, and other characteristic effects of lobotomy occurred because the patient regressed back to a younger mental age. But at the same time, Freeman did not even imagine that damage could be caused to the individual. Rather, he believed that the patient would eventually “grow up” once more: re-adulting would occur quickly and ultimately lead to complete recovery. And he suggested treating the sick (even adults) in the same way as naughty children would be treated.

History of discovery and development

The idea of lobotomy belonged to a Portuguese physician named Egas Moniz (or Moniz). This doctor participated in a congress of neurologists in 1934, where he was supposed to present his work on angiography. At the congress, he became interested in the idea of two colleagues - doctors Jacobsen and Fulton. They talked about their experiment on a monkey named Becky, who suffered from a neurological disorder. Doctors operated on the poor monkey, removing one of its frontal lobes and also destroying associative connections in the frontal region. As a result, the previously aggressive and irritable Becky became quiet and showed few signs of anger. Monitz expressed the idea of carrying out a similar operation on humans, which shocked everyone present. But already on November 12, three months after the end of the congress, Moniz performed the world's first lobotomy on a patient suffering from melancholy and paranoia. He and his assistant drilled two holes in the skull, through which they injected alcohol into the perifrontal region of the brain, which destroyed absolutely all connections between these areas of the brain. After some time, they announced a significant improvement in the patient’s well-being, and over the next five weeks they performed 6 more such operations. Subsequently, from operation to operation, the procedure became more and more improved. But their results turned out to be contradictory. Improvements were observed in 7 patients out of 20 to a significant extent, in another 7 they were weakly expressed, and in 6 no changes were observed at all. But studies by other doctors have shown that the likelihood of symptoms returning or death is very high. Nevertheless, Monitz continued to actively research the effect of lobotomy on the psyche, for which he even received the Nobel Prize in 1949 as a person who contributed to the cure of certain types of severe psychoses.

Development of the concept of surgical interventions

Monitz's ideas also interested other doctors around the world. In the United States, the first lobotomy was performed by Walter Freeman and James Watts. But, unlike Monitz, their methodology was different. The entire intervention was limited to inserting an “ice pick” through the patient’s eye socket into the brain, after which the frontal lobe was cut with one movement of the instrument. It was this method of intervention that later became known as transorbital lobotomy. To increase the effectiveness, anesthesia during surgery was administered using electric shock. And, like Monitz, his American colleagues announced the successful completion of the experiment. In total, about 3,500 operations were performed.

Surgical theater

It is believed that Freeman was too happy to be able to legally perform transorbital lobotomies on all patients indiscriminately. He did not complete the procedure in ten minutes - somehow not enough for a complex brain operation, even if it was the most useful operation in the world...

He once performed 25 lobotomies in a day. It was he who first figured out the “humane” use of electric shock to perform operations while patients were unconscious. Worse, Freeman would sometimes lobotomize both sides of his brain just to show off. It is impossible to say exactly how many people he ruined their lives.

Distribution and popularity of psychosurgical operations

Soon, new methods of treating mentally ill people were already widely used in many hospitals. The Soviet Union was not spared this phenomenon either. Research in the field of psychosurgery was then carried out on 400 patients. After studying a number of operations, it was revealed that the consequences for the human psyche after a lobotomy are very severe, in addition, the unfoundedness of this theory and very contradictory research results contributed. As a result, in 1950, lobotomy was officially banned in the USSR.

But in some countries, such as India, Norway, Finland, Belgium, France, Spain and Sweden, lobotomy was practiced until the late 80s. The Committee for the Protection of Humans from Psychosurgical and Behavioral Research, created in America, made a great contribution to debunking the myth about the usefulness of such operations. It was formed in 1977. This body ruled that lobotomy was a way to control minorities and individuals, and also declared it to be ineffective based on research results. Although it was recognized that a small percentage of operations led to positive results.

Complications of lobotomy

It can be said that those cases where a lobotomy cured a mental illness without causing damage to health were quite rare. In most cases, the long-term results of lobotomy were very sad. What consequences developed after the lobotomy? Let's list:

- infectious complications (meningitis, encephalitis);

- epileptic seizures;

- violations of control over the function of the pelvic organs (urination and defecation);

- muscle weakness in the limbs (paresis and paralysis);

- loss of sensation;

- speech disorders;

- a significant decrease in intelligence, emotional dullness (patients after surgery were compared to domestic animals and called “vegetables”);

- sudden increase in body weight;

- death (up to 6% of all cases).

As we see, the elimination of mental illness by lobotomy was not always comparable to the other “effects” of such operations. And to be completely frank, lobotomy did not always cure psychiatric illness. According to statistics, for a third of the operated patients the operation was useless, for another third it was accompanied by severe complications, and only another third of the patients received some kind of therapeutic effect.

Technology

Having understood what a lobotomy is and why such an operation is needed, it is worth mentioning a little about the methodology for performing it.

Since the brain can biologically cope with some minor damage, removing the frontal lobes without craniotomy can be done without significant harm. At its core, a lobotomy is such a simple operation that even a person who does not have specific medical knowledge can perform it. The whole operation was divided into three stages:

- The first stage - the area of skin above the eye was cut, first it was necessary to treat it with an anesthetic. In general, it was not recommended to use anesthesia during such operations, since the eye must respond adequately to the intervention.

- Then a thin and sharp instrument was inserted through the eye socket at an angle of 15020 degrees. With a simple movement, the frontal lobes were cut out, and since brain tissue is impervious to pain, the patient only felt discomfort in the eyeball.

- After removing the instrument, a probe with a tube was inserted into the incision to remove blood and cell masses. The incision was sutured, and the patient could return to normal life after a week.

Informed consent

Nowadays, doctors must first inform the patient about what will be done, what the risks and possible complications are, and only then begin complex physical or mental treatment. But in the days of lobotomy, patients had no such rights, and informed consent was treated carelessly. In fact, the surgeons did whatever they wanted.

Freeman believed that a mentally ill patient could not give consent to a lobotomy, since he was not able to understand all its benefits. But the doctor did not give up so easily. If he could not obtain consent from the patient, he went to relatives in the hope that they would give consent. To make matters worse, if the patient had already agreed but changed his mind at the last minute, the doctor would still perform the operation, even if he had to “turn off” the patient.

Alternatives

Fortunately, after it was declared that lobotomy was a barbaric and inhumane crime against humans, more humane ways of curing mentally unstable and sick people appeared. Increasingly, they began to resort to the previously popular electroconvulsive therapy; the drug “Aminazine” was also synthesized, which showed much greater effectiveness. And in general, psychopharmacology began to be more actively used for treatment, and physical effects on the brain were given secondary importance. The protests of so many relatives and friends of those who were lobotomized were finally satisfied.

Patient monitoring

Moniz treated patients and monitored their behavior just a few days after breaking the connections in their heads. Many believe that the criteria for determining whether a patient was truly normal were biased: the doctor really wanted the result to be positive. Let's be clear: Moniz found improvement in most patients because that's what he wanted to find. Freeman, although he practiced perhaps a more barbaric method, worked with patients after surgery. He did not abandon them until his death.