Brain dysfunction can have serious consequences. One example is hallucinations in Parkinson's disease. Similar phenomena can develop in 20-60% of people suffering from Parkinson's disease. Most often, hallucinations occur under the influence of external factors, but their source can also be internal.

Thus, the neurodegenerative process that develops in nerve cells involved in the synthesis of dopamine most often leads to psychotic disorders. Taking the medications most commonly prescribed for Parkinson's disease incorrectly can also cause hallucinations.

The first signs of the disease

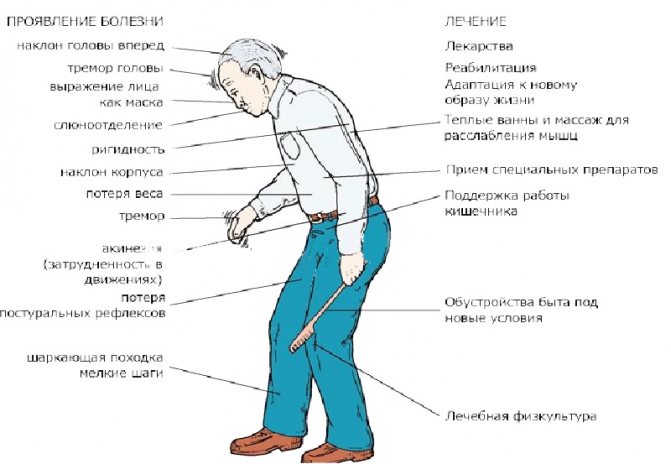

Any disease causes some inconvenience. Parkinson's disease is characterized by more than just body tremors and loss of coordination. This disease causes a lot of discomfort to both the patient and the people around him.

The disease is caused by the progressive destruction of neurons that produce dopamine, a biologically active substance that facilitates the transmission of impulses from a nerve cell between neurons.

Dopamine ensures human cognitive activity. With insufficiency of dopaminergic transmission, increased inertia of the patient occurs, which manifests itself clinically in the slowness of cognitive processes.

At the initial stage, the disease manifests itself mainly as neuropsychiatric disorders. This may be a depressive state, increased fatigue, uncontrollable irritation. Symptoms such as sleep disturbances and apathetic state are also likely. Over time and the gradual development of the process, a problem in the form of hallucinations may well arise.

Types of hallucinations

The word “hallucination” comes from the Latin word meaning “delusion.” At its core, this phenomenon is a disorder of perception, manifested in the form of various sensations and images that arise involuntarily, while objects are absent in reality. Hallucinations can manifest themselves in various forms:

- visual character;

- auditory;

- taste;

- tactile;

- olfactory;

- visceral.

Those suffering from Parkinson's disease most often experience visual visions, a feeling of someone's presence, and a state of delirium. Hallucinations in the form of visual images are the most common guest, but there is a possibility of a complex manifestation.

During visual hallucinations, the patient sees, quite realistically, burning fire, smoke, various things, he can see animals, fantastic creatures in the form of monsters, and even entire scenes with many participants, even natural disasters. In terms of form, visions can be either moving or stationary, display one picture or vary in content. Most often, such hallucinations occur in the evening or at night.

A patient experiencing auditory hallucinations may hear voices, words, or conversations of varying volumes. The content of these “voices” can be very different. This is what poses a particular danger, since the patient can take any “order” or “advice” as a guide to action and cause a lot of trouble. Auditory hallucinations appear most often in a quiet environment, when the patient is completely alone.

Sometimes various hallucinations are combined and accompanied by delusions. The appearance of hallucinations can be guessed by the patient’s changed behavior. He becomes alert, listens, responds to a “voice” that only he can hear, or, conversely, tries to close his ears in the absence of external sound stimuli. When visual visions occur, the patient seems to be looking closely at something, and his facial expression quickly changes.

With true hallucinations described above, the patient cannot distinguish them from real objects and persons. It seems to him that all this is really happening. There are cases of pseudohallucinations when the patient considers them unnatural, artificially created specifically for him.

Source of origin

The complex biochemical reactions that occur in the brain of a person with Parkinson's disease are the main cause of hallucinations. These reactions occur completely naturally, but the presence of any pathologies changes the usual course of the process. As a result, mental disorders develop, and with them come hallucinations.

Hallucinations owe their occurrence not only to mental disorders. Recently, you can hear about the effect of dopa drugs, which are actively used to treat Parkinson’s disease.

The processes occurring in the human brain are an area accessible to understanding only by a very narrow circle of doctors. Parkinson's disease causes abnormalities in the process of serotonin metabolism. These disorders are corrected with the help of a variety of medications, including dopa-containing ones. The latter may well cause a lack of serotonin, which stimulates the occurrence of hallucinations in patients.

Certain special medications prescribed for Parkinson's disease provoke mental disorders, especially the so-called dopaminomimetics and anticholinergics. The very first sign of such an effect of a medication, as a rule, is a state of anxiety. Over time, visual hallucinations also develop. Sometimes at night, mostly when waking up suddenly. This is the most common case. In such a situation, they are short-term in nature and appear only when a person moves from a state of sleep to wakefulness.

Anyone can wake up in the middle of the night and immediately fall asleep. In the morning he won’t even remember that he woke up. People with Parkinson's may experience visions of animals or strangers standing by the bed upon such awakening. Such phenomena frighten the patient and dissipate only with final awakening. Vivid, memorable dreams that are repeated quite often may be typical for patients. Over time, such violations tend to increase. Ultimately, they are complemented by mental disorders even in the waking state. The treatment of such patients is very difficult to predict.

Modern medicine is successfully addressing the issue of developing drugs that compensate for this effect or prevent hallucinations in Parkinson's disease.

The main condition for a successful resolution of the issue is timely examination of the patient by the attending physician and adjustment of the course of treatment.

Parkinson's disease: treatment of psychotic disorders

laesus_de_liro

Often a neurologist has to deal with a situation where a patient with Parkinson’s disease (especially at stages 3–4 (5) according to Hoehn-Yahr) develops psychotic symptoms, or rather hallucinations, night illusions.

In this situation, the prescription of antipsychotics - that is, neuroleptics - contradicts the principles of anti-parkinsonian therapy, since they intensify the phenomena of parkinsonism. How to deal with this situation can be answered in the article “Features of treatment of late stage Parkinson’s disease” Doctor of Medical Sciences, Prof. O.S. Levin, N.N. Shindryaeva, A.K.

Ivanov, published in the journal “Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after. S.S. Korsakova" No. 8 – 2009:: ... Psychotic disorders are observed in approximately 40% of patients with Parkinson's disease (PD), more often at a late stage of the disease.

Although in the vast majority of cases they are provoked by changes in the treatment regimen, the main prerequisite for their occurrence is a degenerative process involving limbic structures and cholinergic neurons. The most common type of psychotic disorder is visual hallucinations.

Visual hallucinations in most cases occur against a background of preserved orientation and criticism (the so-called “benign hallucinosis”) and require systematic correction of the treatment regimen.

First, reduce the dose or discontinue the recently prescribed or least useful drug, often in the following order: anticholinergic - selegiline - dopamine receptor agonist - COMT inhibitor. As a result, the patient can “stay” only on the drug levodopa.

Sometimes you have to sacrifice the dose of levodopa, which is associated with an increase in motor defect. If antiparkinsonian therapy is not corrected in a timely manner, hallucinations can become threatening, criticism decreases, and delusional disorders develop.

Ultimately, delirium may develop, requiring hospitalization of the patient and a careful search for other (in addition to drugs) causes of the psychotic episode (for example, infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, or other metabolic disorders).

In these cases, along with correction of the antiparkinsonian therapy regimen, antipsychotic correctors are necessary. The drug of choice is the atypical antipsychotic clozapine, 6.25 – 7.5 mg per day. If it is intolerable or ineffective, quetiapine is used, 25–200 mg per day. Both drugs provide an antipsychotic effect without the risk of increasing parkinsonian symptoms (as is the case with typical antipsychotics). Cholinesterase inhibitors (rivastigmine, galantamine, etc.) also have antipsychotic activity in PD. Their use sometimes allows one to avoid the use of antipsychotics. Under the “cover” of an atypical antipsychotic and/or cholinesterase inhibitor, it is sometimes possible to increase the dose of levodopa to the optimal level.”

clozapine

(Clozapine) – trade names: azaleptin and leponex;

azoleptin (Azaleptin) – 1 table.

= 25 mg / 100 mg; method of administration and dose: orally, after meals, with a small amount of liquid, 2 - 3 times a day; single dose for adults – 50 – 200 mg, initial daily dose – 150–300 mg, average daily dose – 200 – 400 mg, highest daily dose – 600 mg; the dose is selected individually, starting with the administration of small doses (25 mg) and gradually increasing them by 25 - 50 mg per day until a therapeutic effect is obtained; in mild forms of the disease for maintenance therapy, as well as in patients with liver or kidney failure, chronic heart failure, and cerebrovascular disorders, it is prescribed in lower daily doses (20–200 mg); the staged nature of the manifestation of the therapeutic effect should be taken into account: the rapid onset of hypnotic and sedative effects; relief of anxiety, psychomotor agitation and aggressiveness (after 3 – 6 days); antipsychopathic effect (after 1–2 weeks); effect on symptoms of negativism (after 20 – 40 days); after achieving a therapeutic effect, they switch to a maintenance course (source: rlsnet.ru);

leponex

(Leponex) – 1 table. = 25 mg / 100 mg;

method of administration and dosage: psychosis in Parkinson's disease (in cases of ineffectiveness of standard therapy): the initial dose of clozapine should not exceed 12.5 mg/day (1/2 tablet of 25 mg), it should be taken in the evening; then the dose should be increased by 12.5 mg, no more than 2 times a week, to a maximum dose of 50 mg; a dose of 50 mg can be prescribed no earlier than the end of 2 weeks.

after starting treatment; It is preferable to take the entire daily dose in 1 dose in the evening; the average effective dose is on average 25 – 37.5 mg/day; in case of treatment for at least 1 week.

a daily dose of 50 mg does not provide a satisfactory therapeutic effect; a further cautious increase in the daily dose by no more than 12.5 mg per week is possible; the dose of 50 mg/day can be exceeded in exceptional cases. Do not exceed the dose of 100 mg/day.

; Dose increases should be limited or delayed in the event of orthostatic hypotension, severe sedation, or confusion; During the first weeks of treatment, blood pressure monitoring is necessary; increasing the dose of antiparkinsonian drugs (levodopa), if indicated based on an assessment of motor status, is possible no earlier than 2 weeks after complete relief of psychotic symptoms; according to a 2-year study in patients with Parkinson's disease, during therapy with Leponex® with relief of psychotic symptoms, in order to improve motor functions, it is possible to increase the dose of levodopa by 17–68% of the initial dosage (over 15 months, an improvement of 11– 22% on the motor scale); if this increase causes a reappearance of psychotic symptoms, the dose of Leponex® can be increased by 12.5 mg per week to a maximum dose of 100 mg/day, taken in 1 or 2 divided doses (see above); upon completion of therapy, it is recommended to gradually reduce the daily dose by 12.5 mg no more than once a week (preferably every 2 weeks); treatment should be stopped immediately if neutropenia or agranulocytosis develops; in this situation, careful psychiatric observation is necessary, because symptoms can quickly recur (source: rlsnet.ru).

quetiapine

(Quetiapine) – one of the trade names – Seroquel® (Seroquel® – 1 tablet = 25 mg / 100 mg / 200 mg).

Source: https://laesus-de-liro.livejournal.com/182429.html

Treatment problems

Unfortunately, it is currently impossible to completely cure parkinsonism. However, it is quite possible to reduce its symptoms. This should only be done by an experienced specialist. Self-medication in this matter is completely inappropriate and can be dangerous.

The treatment regimen adopted by modern specialists almost always includes antipsychotics. At the same time, few people think about the consequences of such treatment.

Under the influence of antipsychotics, dopamine receptors in the brain are blocked, and in different parts of it. If the blockade occurs in the limbic structures, psychotic phenomena are stopped by haloperidol.

Blockade of dopa receptors in the nigrostriatal system can simultaneously lead to the development of drug-induced parkinsonism. In this case, the patient finds himself in a contradictory situation where each of the drugs is necessary for treatment, but at the same time aggravates the patient’s condition. The solution to the issue may be to find a compromise when choosing a specific medicine and a safe dose.

Despite numerous recommendations in the field of folk remedies and laudatory reviews of alternative medicine methods in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, both the patient himself and his relatives must understand that such deviations and disruptions in mental functioning are amenable only to highly specialized professional therapy. You will need to consult an experienced doctor with subsequent medical support throughout the entire course of treatment.

Psychosis in people with advanced Parkinson's disease: expert advice

As Parkinson's disease progresses, 60 percent of people develop symptoms of psychosis (according to a 12-year study published in the Archives of Neuroscience

in 2010 year). For caregivers, these symptoms may seem sudden, alarming, and difficult to treat.

Fortunately, the right medications can help treat or reduce the symptoms of psychosis. And knowing how to respond can calm difficult behavior patterns.

We spoke to two Parkinson's disease experts about symptoms, causes and available treatments, and got tips for carers on how to deal with psychotic conditions.

Typical symptoms

People with psychosis may see, hear, smell things that do not exist or appear to others, such as someone spying on them. This makes them anxious or even aggressive.

Joseph Yankovich, MD, FAAN, professor of neurology in the movement disorders department and director of the Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, reports.

"These symptoms tend to appear in the later stages of Parkinson's disease, especially when the patient begins to develop cognitive deficits while taking multiple medications," says Dr. Jankovic.

Common reasons

"Medicines used to treat symptoms of Parkinson's disease, such as levodopa and dopamine agonists, increase dopamine levels, which can cause hallucinations and delusions," says Dr. Jankovic. People with a syndrome called behavioral sleep disorder REM, in which they physically experience vivid dreams, are also at higher risk of psychosis, he says.

Another trigger could be a systemic disease or an unfamiliar environment, says Steven Grill, MD, PhD, co-founder of the Parkinson's and Movement Disorders Center of Maryland. If a person develops pneumonia or a urinary tract infection and needs to be hospitalized, for example, symptoms of psychosis may become more severe.

Adjusting drug treatment

At the first signs of psychosis, the neurologist can adjust the patient’s treatment. For example, the anticholinergic drug Trihexyphenidyl (Artane) can cause or worsen symptoms of psychosis, Dr. Grill says.

Dr. Jankovic adds, "Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole [Mirapex], ropinirole [Requip], and rotigotine [Neupro] are more likely to cause hallucinations than levodopa, so we may want to reduce or stop prescribing these medications," he says.

If hallucinations persist, neurologists may reduce the dosage of levodopa, but this may worsen symptoms, says Dr. Jankovic. To avoid levodopa withdrawal, doctors may add an antipsychotic such as quetiapine (Seroquel).

"Most antipsychotic drugs should not be taken by people with Parkinson's disease because they block dopamine receptors and increase symptoms," he says, adding that quetiapine is an exception.

Doctors may also prescribe the antipsychotic clozapine (Clozaril), but the drug is usually seen as a last resort because it can cause low white blood cells.

A promising new drug

A new drug called pimavanserin (Nuplazid) has shown promising results in clinical trials for treating psychosis in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease and could be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as early as this year, Dr. Jankovic says.

Most antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors, he explains. “Pimavanserin binds to serotonin receptors so it does not worsen parkinsonism or cause involuntary movements,” he says.

How to manage psychotic behavior

- Keep calm.

Caregivers can help alleviate symptoms of psychosis by adopting a calm, supportive and reassuring demeanor, says Dr. Jankovic. Not confrontational or aggressive, he adds. - Create a safe environment.

A quiet, well-lit environment at night may also reduce the frequency of visual hallucinations. "Darkness creates shadows, and people can mistake them for anything," says Dr. Grill. - Don't focus your attention.

"The caregiver must learn not to make a big deal about it," says Dr. Grill. "So if someone says, for example, 'I just saw a rat,' the caregiver might say, 'Maybe you were imagining it.' And then just get busy and change the subject.” - Seek help when needed.

If a person becomes violent or uncontrollable and you fear for his or her safety (or your own), don't hesitate to ask others for help. - Have access to anti-anxiety medications.

Have anti-anxiety medications such as alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), or lorazepam (Ativan) on hand in case of a severe psychotic episode. “Be sure to discuss these strategies with the patient's neurologist or psychiatrist, who can help you implement them.”

Source: https://www.nevrologist.ru/psikhoz-u-lyudej-s-progressiruyushhej-boleznyu-parkinsona/