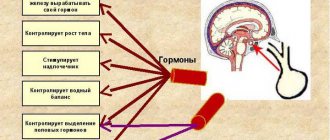

The pituitary gland is the most complex organ of the human body, which is responsible for neuroendocrine regulation. It is located at the base of the skull in the sella turcica and has three lobes that produce different hormones.

The pituitary gland, also called the medullary appendage or pituitary gland, having such tiny dimensions (its mass is only 0.5-1 g), is of great importance for the entire human body. The heterogeneous structure of the pituitary gland leads to malfunction of internal organs and systems.

This is explained by the fact that the vital hormones it produces, such as prolactin, somatotropin, glycoproteins, endorphins and others, affect the functioning of the entire human body.

Causes

Heterogeneity of the pituitary gland is associated with the appearance of compactions: cysts, adenoids and tumors. The formation of adenoma occurs when hormones are formed by pituitary cells. It can develop in women and men aged 25 to 50 years, and very rarely appears in children.

The cyst can be congenital or acquired and is a small bubble of fluid. Most often these are benign formations. However, if left untreated, they usually develop into malignant tumors or adenocarcinomas.

What are the complications, and what preventive measures are followed?

If the treatment was incorrect or the disease is advanced, this provokes:

- abscess;

- cancer formation;

- state of shock;

- internal bleeding;

- duodenal stenosis;

- pleurisy.

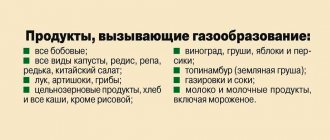

To get rid of problems with the organ, you should seriously adjust your diet. It is important to reduce or completely eliminate foods that irritate the organ. Make the patient's diet complete and balanced. And also give up nicotine and alcohol, exercise, and lead a healthy lifestyle.

Symptoms

As a rule, the disease is not felt at all. Symptoms of the abnormality may begin to appear as the tumors increase. Signs of this disease are:

- Reduced field of vision and sharp deterioration of vision.

- Regularly occurring headaches localized in different places.

- Impaired motility of the eyeballs.

- Failure of the menstrual cycle and sexual dysfunction associated with hormonal imbalance.

- The appearance of neurological abnormalities: numbness, convulsions, epileptic attacks.

- Circadian rhythm disturbances and poor sleep.

- Loss of orientation in space.

What does diffuse tissue heterogeneity mean?

The pituitary gland is small in size and weighs only 0.5-1 g. To determine any abnormalities, an ultrasound or tomography is required. The results of the examination may indicate that the structure of the pituitary gland during the study is diffusely heterogeneous. What does this diagnosis mean?

Why does the pituitary gland have a heterogeneous structure?

The diagnosis is diffuse tissue heterogeneity, indicating unequal reflective properties of tissues. The reasons for this are:

Adenomas.

- Cystic formations.

- Tumors.

Consequently, the structural heterogeneity of the pituitary gland means that in some areas the tissue has compactions. In most cases, we are talking about benign education. But in the absence of proper treatment, tissue degeneration and the formation of adenocarcinoma, a malignant tumor, are possible. This happens extremely rarely, but the danger of degeneration still exists.

Signs of a heterogeneous structure of the pituitary gland

Fine-focal heterogeneity often does not appear. Symptoms of the disease appear when the tumor tends to increase. Signs indicate the localization of the compaction.

The main symptoms of the disease are:

- A sharp deterioration in vision - first the field of vision decreases. When visiting an ophthalmologist, a deterioration in the motility of the eyeball is detected.

Headaches are not relieved by conventional analgesics.

- Neurological signs - a large tumor leads to the appearance of convulsions, numbness, and epileptic seizures.

- Changes in hormonal levels - the consequence of heterogeneity of pituitary gland tissue is sexual dysfunction, menstrual irregularities, and inability to become pregnant.

Additional signs indicating that there is heterogeneity of the pituitary gland are disturbances in a person’s circadian rhythms, insomnia, and in severe cases, loss of orientation in space.

Why is diffuse heterogeneity scary?

The heterogeneous structure of the pituitary gland indicates that a tumor is developing in the area of the pituitary gland. The consequences of the development of the resulting anomaly depend on its nature, volume and degree of malignancy.

How is it determined

Due to the small size of the pituitary gland, it is quite difficult to detect its diffuse deviation. Ultrasound and MRI can cope with this task. Only thanks to modern techniques can one detect the degree of density of pituitary tissue and identify the fact of the development of nodes, adenomas and other neoplasms.

The result of the echocardiography of ultrasound and magnetic tomography is a description of the structure of the pituitary gland. The result of the study is considered positive, the conclusion of which is “the echostructure of the pituitary gland is homogeneous, without changes.”

The diagnosis of “heterogeneous structure” indicates existing abnormalities in the pituitary gland. As a rule, the exact location of the formations is indicated and its size is indicated.

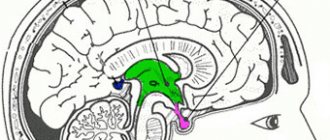

MRI of the pituitary gland: what the organ looks like in normal condition

First of all, practicing doctors should know the characteristics of normal indicators when performing an MRI of the pituitary gland:

- in the frontal plane, the shape of the pituitary gland is close to rectangular;

- the lower contour of the pituitary gland follows the shape of the sella turcica, and the upper contour can be horizontal, convex or concave;

- in the sagittal plane, the shape of the normal pituitary gland is ellipsoidal, its lobes are well differentiated;

- the sagittal and transverse dimensions are determined by the dimensions of the sella turcica, and the vertical – about 4-8 mm;

- in frontal sections the pituitary gland is often symmetrical;

- The pituitary infundibulum is normally located in the midline.

Consequences of the heterogeneous structure of the pituitary gland

The structure becomes heterogeneous from the moment of formation of various compactions. The consequences of this condition of the pituitary gland depend on the cause of its occurrence, the degree and volume of malignancy.

A patient with the smallest formations (the size of the adenoids varies up to 10 mm) experiences virtually no discomfort, or it only manifests itself for a short time.

As tumors grow, the following symptoms may occur:

- Rapid deterioration of vision and even complete loss of vision;

- Dizziness and loss of coordination;

- Numbness of the limbs;

- Epilepsy attacks;

- Disorders of the reproductive and reproductive systems.

In the case of rapid growth of malignant tumors, the patient is given a disappointing prognosis. Most often, people with hypertension, excess weight, and diabetics are at risk. Diffuse changes in the pituitary gland most have negative consequences for the reproductive system of the body.

So, for women this is a disruption in the menstrual cycle and problematic conception. Men with this diagnosis experience erectile dysfunction.

In children, changes in the structure of the pituitary gland are associated with gigantism and dwarfism (with excess and lack of somatotropin).

What may be associated with hypotrophy of the pituitary gland?

The main reasons leading to hypotrophy of the pituitary gland are:

- congenital pathology, which leads to compression of this gland by surrounding brain tissue,

- increased intracranial pressure,

- menopause after frequent pregnancies ending in abortions,

- ischemic necrosis of the pituitary gland (Simmonds syndrome), associated with massive bleeding during childbirth,

- autoimmune processes,

- surgery or radiation therapy to this area of the brain.

Interestingly, during pregnancy the pituitary gland increases significantly in size, not always returning to its original state after childbirth. Therefore, during age-related involution, its significant decrease may occur.

How to diagnose correctly

The appearance of neurological symptoms is not 100% a consequence of the heterogeneous structure of the pituitary gland. To exclude other causes of illness, it is necessary to undergo several diagnostic procedures:

- Radioimmunological testing of blood, revealing the level of hormones in it.

- Ultrasound. This is a primary procedure especially for newborn babies.

- Magnetic resonance imaging. In modern medicine, this is the most informative method of diagnosis. Allows you to detect compactions measuring only a few millimeters in the heterogeneous structure of the organ.

Thanks to the volumetric image, the structure of the pituitary gland can be examined in more detail, seeing the smallest changes and tendencies towards deformation.

If the development of malignant tumors is suspected, examination on a tomograph using a marker is necessary. This procedure helps to identify the nature of the tumor.

Signs of tumor formations during MRI of the pituitary gland

When performing MRI of the pituitary gland, the following signs of tumors of the chiasmatic-sellar region are clearly visualized: deformation of the bottom of the sella turcica, asymmetry and bulging of the contour of the pituitary gland, displacement of the infundibulum, heterogeneity of the structure of the organ. All these signs do not unambiguously indicate the presence of a tumor, so they must be analyzed together with the results of dynamic observation and the characteristics of the clinical picture of the pathology in a particular patient. Based on the nature of their spread, pituitary tumors are divided as follows:

- endosellar - do not extend beyond the sella turcica;

- suprasellar - grow into the suprasellar cistern;

- parasellar - grow into cavernous sinuses;

- infrasellar - grow into the sinus of the main bone;

- retrosellar - grow into the brain cistern, destroying the back of the sella turcica;

- antesellar - grow into the cells of the ethmoidal labyrinth, mediobasal sections of the frontal lobes and nasal passages.

Therapy methods

Often, it is possible to diagnose a heterogeneous structure only in a situation where the grown compactions begin to affect neighboring tissues. To select the correct treatment, the doctor needs to study the results of all tests, and the patient must undergo a tomography examination.

If the volume of the compaction is small, as a rule, regular monitoring of its increase is prescribed. If there is no tendency for tumor cells to grow, there is no need for drug treatment.

Medication therapy should only be prescribed by the attending physician. With the right blocking treatment, many of the consequences of the disease are suspended and even eliminated: potency and reproductive abilities can be restored.

Preventive measures and conservative therapy can stop the growth of tumors and balance the patient’s hormonal levels. Types of seals that cannot be treated with medication are removed during surgery and subsequent radiation therapy.

The key to complete recovery or stabilization of the pituitary gland is early seeking qualified medical help. The normal functioning of this part of the brain determines the patient’s health and the functioning of the body’s internal systems.

Signs of non-tumor pathologies during MRI of the pituitary gland

Depending on the results of an MRI of the pituitary gland, the following non-tumor pathologies of this organ can be suspected:

- thinning of the pituitary gland, its flatness along the bottom of the sella turcica due to sagging of the chiasm cistern allows one to suspect empty sella turcica syndrome;

- in the presence of diabetes insipidus, the patient may experience signs of inflammatory or tumor damage to the hypothalamic-pituitary system, as well as the absence of a hyperintense signal from the neurohypophysis in idiopathic diabetes insipidus;

- ectopia of the neurohypophysis, hypoplasia of the adenohypophysis, and aplasia or hypoplasia of the pituitary stalk in most cases are signs of GH deficiency.

Share:

Inactive pituitary adenomas and pathology of the reproductive system in women

V.G. Shlykova, A.A. Pishchulin, A.A. Bulatov

Endocrinological Research Center of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow

An analysis of modern ideas about the mechanisms of development of “inactive” pituitary adenomas (PAA), which are not clinically manifested by symptoms of hypersecretion of pituitary hormones, is presented.

The frequency of the combination of NAH and disorders of the reproductive function of women, primarily polycystic ovary syndrome, indicates a pathogenetic connection between these types of pathology. From this perspective, the issues of diagnosing NAH, approaches to treating pathology of the reproductive system in combination with NAH, as well as the pituitary adenoma itself are considered. Pituitary adenomas are benign tumors of the adenohypophysis , which account for about 15% of all intracranial tumors [8, 66]. At autopsy of a pituitary adenoma

found in 10-20% of those who died from diseases not associated with damage to the pituitary gland.

Pituitary adenomas

that occur without clinical manifestations of hypersecretion of pituitary hormones are called “inactive” (non-active) pituitary adenomas (NAG). In the literature, the terms “clinically nonfunctioning adenomas” or “silent” adenomas are also used. NAGs make up 25-30% of all pituitary tumors [39], while with suprasellar localization their percentage increases to 70 [50, 55].

It is necessary to distinguish between the concepts of NAG and “incidentaloma”; the latter is often found in foreign literature [51]. Incidentalomas (incident-accident) are tumor formations discovered in any organ by chance during a more detailed examination of the patient. Pituitary incidentalomas

can be both NAG and

hormonally active adenomas

, for example,

prolactinomas

.

Pituitary adenomas are classified according to morphological characteristics, hormonal activity, and degree of spread [66]. Based on their size, pituitary tumors are divided into microadenomas (less than 1 cm in diameter) with intrasellar growth and macroadenomas with suprasellar spread (diameter more than 1 cm).

In women, NAG is often combined with pathology of the reproductive system. 88% of women with NAH have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and 23% have secondary hypogonadism with amenorrhea [4]. More often, patients who have pituitary microadenomas a gynecologist , since when the tumor is large, neurological and ophthalmological disorders are leading, and disorders of the reproductive system fade into the background.

This article discusses the pathogenetic connections between NAH and the pathology of the reproductive system in women, the issues of diagnosing NAH, as well as approaches to the treatment of pathology of the reproductive system in NAH and the pituitary adenoma itself.

Pathogenesis of NAG and its connection with pathology of the reproductive system

According to modern concepts, based on the achievements of molecular biology, pituitary adenomas, including NAG, are a product of monoclonal proliferation of genetically transformed somatic cells [39, 58, 66]. However, the development of a pituitary tumor is a multistage process that involves, along with somatic mutations in pituitary cells, many other additional factors - hormonal, autocrine and paracrine. Important pathogenetic factors involved in tumorigenesis in the pituitary gland are hypothalamic hormones, neurotransmitters and growth factors [16, 32, 58, 66]. At the same time, it should be emphasized that disorders of hypothalamic regulation and other specified factors, in contrast to oncogenic mutations, most likely only contribute to the development of a pituitary tumor, but are not its direct cause.

Since it has been proven that pituitary cells are capable of producing various growth factors, including basic fibroblast growth factor, which has a powerful mitogenic and angiogenic potential, and have corresponding receptors [66], the possibility of the participation of growth factors in the pathogenesis of pituitary tumors is beyond doubt.

Although there are no clinical signs of hormonal hypersecretion in NAG, such tumors, according to histomorphological and molecular biological studies, as well as studies on cell cultures, have the necessary organelles for the synthesis of hormones and are capable of their synthesis and secretion [7, 17]. NAGs can develop from different cells of the adenohypophysis, but most often they originate from gonadotrophs. More than 80% of these tumors synthesize luteinizing (LH) and/or follicle-stimulating (FSH) hormones or their free - or - subunits. “Silent” corticotrophic, somatotrophic or lactotrophic adenomas are found much less frequently [43]. In 90% of cases, secretory granule proteins—chromogranins A and B and secretogranin 2—are found in NAG cells [41, 45].

As noted above, the largest share in the structure of reproductive pathology in NAH belongs to PCOS. Let us consider modern ideas about the pathogenesis of this disease. According to one theory, PCOS develops as a result of a “vicious” cycle of androstenedione formation [31, 48]. The latter can be partially produced in the adrenal glands and is aromatized in the periphery into estrone. An increase in the level of estrone in the blood leads to an increase in the secretion of LH by pituitary gonadotrophs. LH, in turn, causes or maintains increased ovarian secretion of androstenedione. The second, alternative theory considers PCOS as a form of functional gonadotropin-dependent ovarian hyperandrogenism [31]. According to this theory, the basis for disorders in PCOS is an increase in the intraovarian concentration of androgens. Local increases in androgen levels contribute to follicular atresia and are responsible for anovulation as a result of the direct action of androgens on the ovary. Androgens, entering the bloodstream, cause virilizing changes and the development of hirsutism. Processes that can lead to increased ovarian androgen levels include follicular atresia, which may be either a cause or a result of androgen excess, increased extraovarian androgen production, defects in estrogen biosynthesis from ovarian androgens, and dysregulated androgen secretion, which may result both excessive secretion of LH by the pituitary gland and increased action of LH by insulin, insulin-like and other growth factors [31].

PCOS can be associated with hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance [28, 61]. The following effects of insulin in the ovaries have been described [31]: 1) in vitro stimulation of androgen secretion by the ovarian stroma in women with hyperandrogenism; 2) its synergism with LH in stimulating androgen production by the ovaries in vitro, carried out directly through insulin receptors (insulin receptor mRNA is found in the ovary at all stages of follicle development in the ovary); 3) increasing the production of androgens due to the influence on the complex intraovarian system of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and the proteins that bind them. In addition, insulin can reduce the serum concentration of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which leads to an increase in the level of free testosterone in the blood. The participation of growth factors in the pathogenesis of both PCOS and NAG indicates the similarity of their basic mechanisms.

In NAH, in addition to PCOS, hypogonadism can be observed and functional hyperprolactinemia can be detected [39]. The mechanism for the development of these changes in large adenomas is compression and damage by the tumor to cells producing gonadotropins and/or prolactin (PRL). The second possible cause of impaired reproductive function pathology in NAH is the “crossed pedicle phenomenon” - compression of the portal vessels of the pituitary gland by the macroadenoma and disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary connections. Hypogonadism may be due to the inhibitory effect of PRL on the production of gonadotropins, progesterone and estrogens, as well as on the process of luteinization [5]. After surgical removal of the tumor, decompression of the pituitary cells occurs and hormonal status is often restored. However, when changes in hormonal status are associated with ischemic necrosis of pituitary cells, recovery options after surgery are limited. Apoplexy and sclerosis can also occur in the tumor tissue itself (often with long-term therapy with bromocriptine). In these cases, remission is clinically noted, and with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (CT or MRI, respectively) a functionally inactive cystic adenoma is diagnosed in the pituitary gland.

Reproductive system dysfunction in NAH may be caused by abnormal, non-cyclic production of gonadotropins or their subunits by adenoma cells. The physiological role of free gonadotropin subunits remains unclear. However, data have appeared in the literature suggesting the possibility of independent influence of the α-subunit of glycoprotein hormones on the reproductive system [52].

A certain role in the pathogenesis of NAH may belong to peripheral links in the ovarian-hypothalamus-pituitary feedback system. It is known that chronic hyperestrogenism leads to hyperplasia of pituitary cells and can cause the development of adenoma [34]. It is likely that conditions accompanied by an increase in the content of estrogen in the blood (including PCOS) can contribute to the development of pituitary adenomas.

All types of physiological (menopause) or pathological (exhausted or resistant ovarian syndrome) ovarian hypofunction lead to stimulation of the secretion of gonadotropins by the pituitary gland, and such a load on pituitary cells can cause compensatory cellular hyperplasia and possibly contribute to the development of adenoma. In general, an analysis of the mechanisms of development of NAH and reproductive dysfunctions often combined with them, primarily PCOS, indicates the existence of a pathogenetic relationship between these types of pathologies, which must be taken into account when diagnosing and treating them.

Diagnosis of NAG Unlike hormonally active adenomas, NAG does not have any specific clinical symptoms and does not manifest itself with classic hormone hypersecretion syndromes (Cushing’s disease, acromegaly, etc.)

Small NAGs are more often identified as a finding on cranial radiography.

Microadenomas (including non-functioning ones), unlike macroadenomas, do not manifest symptoms of compression of surrounding tissues by the tumor (neurological and ocular symptoms), however, as with large tumors, hyperprolactinemia may be observed, the origin of which is still hypothetical.

The endocrine manifestation of NAG can be partial or complete (in macroadenomas) hypopituitarism [41, 50, 55]. This often results in menstrual disorders, anovulation and infertility, and decreased libido.

Despite the leading role of instrumental examination methods in the diagnosis of NAG, anamnestic and clinical data help diagnose the presence of adenoma at earlier stages of the disease. When German authors examined 517 patients (311 of them women), it was found that the average anamnestic time for NAH in women was about 2 years, which is significantly longer than in men (1 year) [64].

The most common initial symptoms were oligo- or amenorrhea (in 57.9% of patients), visual field defects (in 11.6% of patients), and headache (in 11.3%). According to other authors [14], menstrual irregularities can occur in 78.3% of patients with NAH.

The most common pathology of the reproductive system in NAH is PCOS. This syndrome includes a whole range of symptoms, among which opsomenorea, infertility, hirsutism and metabolic changes are more common [38].

When examining such patients, chronic anovulation, increased LH/FSH ratio (> 2) and hyperandrogenism are revealed [48]. In recent years, it has been established that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia often occur in PCOS [24, 29].

The leading role in identifying NAG belongs to radiation diagnostic methods. X-ray craniography evaluates signs of increased intracranial pressure and the condition of the sella turcica and areas of calcification. Double contour of the sella turcica, osteoporosis and/or deviation of the back with preserved dimensions of the sella turcica indicate the likelihood of a pituitary microadenoma [3].

For a more accurate diagnosis, CT or MRI is used, with preference given to MRI with gadolinium contrast [47, 62, 68]. To resolve controversial issues, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is recommended [49]. There are results of the successful use of positron emission tomography for the diagnosis of pituitary microadenomas [8]. However, issues of differential diagnosis between NAG and hormonally active adenomas remain beyond the capabilities of imaging methods.

When studying the hormonal status in the blood serum of patients with NAH, there may be a slight increase in the level of FSH, -FSH, -subunit and, less often, LH [1, 2, 33, 39]. LH-secreting tumors are rare, but in this case there may be an increase in testosterone levels. The level of FSH in the blood serum is elevated in approximately 15% of patients, which in 48% of cases is combined with secretion of the β-subunit. Adenomas secreting only the α-subunit occur in 7% of cases [39]. Functional pharmacodynamic tests are essential in the differential diagnosis of NAG. These include tests using drugs that stimulate PRL secretion (with metoclopramide, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, sulpiride, chlorpromazine, insulin hypoglycemia, cimetidine). In order to study the functional reserves of pituitary tropic hormones and for the early diagnosis of microadenomas, tests with thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) are used - the reaction of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), PRL, somatotropic hormone (STG) is studied; with luliberin and estradiol - determine the reaction of gonadotropins; with glucose and arginine - growth hormone; with insulin - growth hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); with metopyrone and lysinvasopressin - ACTH. Most of these samples are used for scientific purposes; their use in clinical practice is limited [5].

The most commonly used tests are TRH and metoclopramide. It is believed that an increase in the PRL level by more than 3.5 times at the 20-30th minute of the TRH test allows one to exclude the presence of prolactinoma. In non-tumor hyperprolactinemia, the peak PRL response to TRH stimulation may be normal or reduced, but the total increase above the initial level is usually higher than in tumor hyperprolactinemia. In the presence of prolactinoma, the PRL response is reduced or absent. There are reports that note the effect of TRH on the release of gonadotropins and the -subunit of glycoprotein hormones in patients with NAH [23, 39, 57].

Metoclopramide (cerucal), being a centrally acting dopamine antagonist, has a stimulating effect on the secretion of PRL. Normally, the maximum secretion of PRL during the test is 10-15 times higher than the initial one. Prolactinoma is usually refractory to metoclopramide, and the basal PRL level is higher (more than 2000 mU/L) than with NAG. With functional hyperprolactinemia, the hormone response to the stimulant may be reduced [6].

A test with luliberin (LH-releasing hormone; LHRH) or its analogs allows you to study the functional reserves of pituitary gonadotrophs and predict the effect of further therapy with these drugs.

Attempts are being made to establish markers specific for NAG. According to some authors, this role can be claimed by: -subunit of glycoprotein hormones, chromogranins A and B and secretogranin 2 [1, 8]. However, this is a subject for further study.

NAG must be differentiated from hormonally active pituitary tumors (somatotropinomas, prolactinomas, ACTH-secreting adenomas, thyrotropinomas, gonadotropinomas). As mentioned above, in the clinical picture of small hormonally active incidentalomas, the classic symptoms of hypersecretion of pituitary hormones may be absent, and changes in hormonal status may be very minor. NAG also needs to be distinguished from other tumors and pathological processes in the central nervous system and in the area of the sella turcica (craniopharyngiomas, neuromas, metastatic foci, various types of calcifications, cysts, inflammatory processes in the pituitary gland, neurohypophysial tumors, etc.). The difficulty of differential diagnosis of pituitary microadenomas and autoimmune lymphocytic hypophysitis deserves special mention, in which (as with CAH) there may be a deficiency of one or another pituitary hormone, up to panhypopituitarism [56, 60] or slight hypersecretion of pituitary hormones (often PRL). It is believed that lymphocytic hypophysitis is an independent process that is not a complication of pituitary adenoma. It is also unlikely that an adenoma could be the result of previous inflammation in the pituitary tissue. The diagnosis of lymphocytic hypophysitis is based on an increase in the size of the pituitary gland (according to MRI) and on findings from a puncture biopsy of the pituitary gland [60]. As markers of lymphocytic hypophysitis, it is recommended to determine antipituitary autoantibodies in the blood, which can occur in patients at the preclinical stage. To preserve the function of the pituitary gland in case of inflammation, glucocorticoid therapy is recommended, since long-term lymphocytic hypophysitis leads to pituitary atrophy [25, 60]. There are known cases of a combination of lymphocytic hypophysitis with microadenoma, confirmed by biopsy, and recently data have been obtained on the possible presence of antipituitary autoantibodies in the blood of patients with NAH, which, however, cannot be considered as tumor markers.

Thus, visual methods for diagnosing NAG are not always reliable, and, therefore, it is necessary to find ways to most accurately verify this pathology.

Approaches to the treatment of pathology of the reproductive system in NAH

Since the main share in the structure of the pathology of the reproductive system in NAH is PCOS, we will consider approaches to the treatment of such a combined pathology. Both conservative and surgical methods are used to treat PCOS.

I. Conservative treatment

Dopamine agonists. In PCOS, disturbances in monoaminergic regulation are found with changes in the ratio of neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine), which can lead to pathological secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone by the hypothalamus [9, 20]. Although this mechanism is not the leading one in PCOS, therapy with dopamine agonists (Parlodel, Abergin) in some cases (more often in the presence of functional hyperprolactinemia) can lead to normalization of ovarian function.

Estrogen-gestagen drugs. When combining PCOS with NAH, special caution should be exercised when using drugs containing estradiol (for example, Diane-35), since the latter can not only cause lactotroph hyperplasia, but also promote tumor growth [34, 53]. In this case, preference should be given to progestin drugs.

Ovulation stimulants. Induction of ovulation in PCOS, when chronic anovulation often occurs, can be carried out with clomiphene citrate (CC). It has been shown that CC has an antiandrogenic effect at different levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian system, but the mechanism underlying its induction of ovulation remains unclear [12].

It is believed that CC blocks estrogen receptors in the pituitary gland and causes their desensitization. The effect of CC depends on the initial level of estrogen in the body. With hyperestrogenism, it exhibits pronounced antiestrogenic activity, while with reduced estrogen saturation it gives a weak estrogenic effect. Although the use of CC in women with PCOS leads to a temporary increase in serum LH and FSH levels [40, 67], this alone is not sufficient to trigger the initiation of folliculogenesis and timely ovulation. It was noted that after 2 days from the start of CC treatment, the level of circulating IGF-1 in the blood, which is a strong mitogenic and metabolic agent, decreases by 30%, and the level of SHSH increases by 23% [22]. This leads to an increase in the level of IGF-1 in the follicle [30]. IGF-1 in the follicle as an autocrine and paracrine stimulator, together with FSH, enhances aromatase activity, increasing the production of estrogen in granulosa cells, which leads to follicle maturation and ovulation [13]. By increasing the level of SHSH, the level of biologically active circulating androgens and estrogens in target cells decreases.

LHRH analogues.

In recent years, synthetic analogues of LHRH have begun to be used for the treatment of PCOS, which at the same time, according to some data [46], can reduce the size of NAG. However, this type of therapy is not widely used in practice due to the lack of complete certainty regarding the effect of LHRH analogues on adenoma, and also, possibly, due to the high cost of these drugs. Long-term treatment with LHRH analogues leads to suppression of gonadotropin secretion and reduces the level of ovarian androgens, and also induces ovulation after discontinuation of the drug. The effect of LHRH analogues is explained by the so-called “down-regulation” phenomenon. Its essence is that long-term pulsed administration of these drugs leads to their binding to LHRH receptors in the pituitary gland. At the beginning of treatment, some of the receptors turn out to be unbound and constant resynthesis of receptors occurs (phase 1 - stimulation - is characterized by a transient increase in the level of LH, FSH and sex steroids in the blood). With continued continuous administration of the drug (about 3 weeks), LHRH receptors cease to be detected (phase 2 - “desensitization” and blockade of LH secretion). When treated with LHRH analogues, the level of FSHG in the blood significantly increases, which helps to optimize the follicular environment. The level of FSH also increases, the level of LH, testosterone (T) and androstenedione (A) in the blood decreases [65], which is an important factor in the induction of ovulation. The most favorable for improving ovulatory function is a decrease in the LH/FSH ratio and the level of T and A in the blood [36, 59]. Currently, a new group of drugs is being studied - LHRH antagonists, which do not provide an initial stimulating effect, but directly, after the first injection, suppress LH secretion [37]. Perhaps their use in the combination of PCOS and NAG will be pathogenetically more justified.

The effect of LHRH analogues on proteins that bind IGF has also been noted. A decrease in the level of IGF-binding proteins in PCOS may increase the amount of free IGF, which potentiates LH-induced androgen synthesis [26].

II. Surgical treatment

An alternative to conservative treatment of PCOS (if it fails) has long been considered bilateral wedge resection of the ovaries [63]. However, despite the effectiveness of this method, when using it, there is a high probability of developing periovarial adhesion, which can cause mechanical (tubal-peritoneal) infertility [11].

In the late 1980s, ovarian electrocautery became more popular [35]. Independent studies using various surgical techniques (laser vaporization, electrocautery) have shown that the development of periovarial adhesion depends on the amount of damage to the ovarian surface. The frequency of adhesion varies from 20 to 80%, and ovulation is restored in 50 to 90% of patients, depending on the technique used [27, 54]. Laparoscopic techniques are used to reduce damage to the ovaries. Some authors recommend reducing the number of diathermy points, as this leads to decreased adhesion and the achievement of pregnancy in a large percentage of cases [15]. It was found that even with the use of unilateral (on one ovary) diathermy, ovarian activity increases in both ovaries. In this case, correction of the disturbed ovarian-pituitary feedback is achieved and normal gonadotropin control over the functioning of the ovaries is restored [18]. Surgical trauma to the ovary is believed to lead to the activation of local production of growth factors, including IGF-1, which, in interaction with FSH, can stimulate the growth of follicles in the uninjured ovary [19]. Electrocautery of the ovaries causes endocrine changes similar to those caused by the administration of LHRH analogues [10].

Normalization of hormonal status allows you to achieve ovulation, and can have a positive effect on the condition of the pituitary adenoma. In clinical practice (archive of the Scientific Research Center of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences - unpublished data), there have been cases of a decrease in the size of the pituitary adenoma or its cystic transformation after normalization of ovarian function. At the same time, after removal of the pituitary adenoma, the reverse development of PCOS may occur [44].

If an asymptomatic pituitary microadenoma is detected in a patient with reproductive dysfunction, surgical treatment is not indicated. In such cases, monitoring using dynamic MRI is recommended to monitor possible tumor growth [39].

Surgical methods of treatment for NAG are used when symptoms of tumor compression of surrounding anatomical structures (primarily the optic nerve and pituitary stalk) develop, as well as when “inactive” adenoma develops clinical and/or biochemical signs of increased hormonal activity that cannot be treated with conservative methods. Currently, the main method of surgical treatment of NAG is transsphenoidal removal of the adenoma [8, 39]. In cases of tumor recurrence, postoperative radiotherapy or proton therapy is used.

Restoration of menstrual function after surgical treatment of NAG was observed in 55% of patients [14]. Favorable prognostic factors for surgical treatment of NAG are 1) adenoma size less than 40 mm, 2) amenorrhea period less than 5 years, 3) normal level of gonadotropin secretion before surgery.

Attempts at conservative treatment of NAG involve the use of bromocriptine (BC) and other dopamine agonists. However, data from different researchers on the effect of CD on the size of NAG vary significantly. Some authors come to the conclusion that it is inappropriate to treat NAG with BC drugs [21], while others [46] indicate a decrease in tumor size when using BC. A similar therapeutic effect has been described with the use of octreotide (a somatostatin analogue), as well as buserelin (an LHRH agonist). On average, a decrease in tumor size was observed in 17% of cases, regardless of the drug used, and corresponded to the effect in the treatment of CD (about 20% of cases) [8]. As noted above, the effect of LHRH agonists with long-term use is based on suppressing the levels of LH and FSH and reducing the level of sex steroids in the blood, which can help restore disrupted relationships between the pituitary gland and the ovaries. However, long-term use of LHRH analogs leads to “desensitization” of receptors in adenoma tissue [42]. LHRH antagonists, unlike agonists, cause the same effects, act immediately after their administration, without an initial stimulating effect [37]. The effectiveness of the use of LHRH agonists in NAH has not been fully studied, and the data available in the literature are contradictory [8, 46]. The effectiveness of LHRH antagonists in this pathology has not yet been studied.

In conclusion, it should be noted that identifying NAG often presents significant difficulties and requires a careful assessment of the clinical picture, a wide range of hormonal studies and pharmacodynamic tests. Management of patients with pathology of the reproductive system in combination with NAG includes long-term dynamic monitoring of the condition of the sella turcica and the adenoma itself using CT or MRI methods, multiple studies of hormonal status, as well as selective selection of therapeutic agents for the correction of pathology of the reproductive system, taking into account their possible effect on the pituitary adenoma .